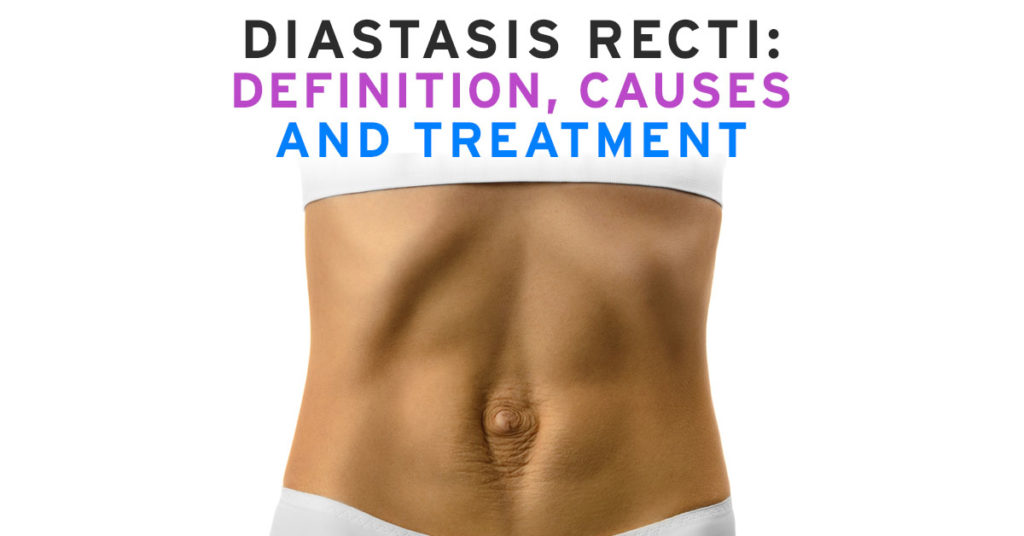

What is Diastasis?

A diastasis recti is a thinning of the fascia known as the linea alba that connects each side of your abdominal wall together. The linea alba runs down the midline from your ribs to your pubic bone and the thinning can be at various locations and varying degrees down the abdominal wall.

![Diastasis [Converted] Types of Diastasis Recti](https://www.coreexercisesolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Diastasis-Converted-scaled-e1615422125239.jpg)

Who Can Get Diastasis Recti?

Research shows that 100% of women at the end of pregnancy have a diastasis recti to accommodate for the lengthening of their abs from a growing belly (Mota et al., 2015) with 60% of women having one at 6 weeks postpartum (Sperstad et al., 2016) and 39% of women still having one at 6 months postpartum (Mota et al., 2015). Basically every pregnant woman will have one with some resolving naturally on their own and others staying around and needing extra help. Research also shows that weight gain, belly size or baby size do not affect the occurrence of diastasis. It is more common than pelvic floor injuries in women after c-section compared to vaginal births.

Outside of pregnancy, babies and young kids (until they develop core, hip and shoulder strength) and people who have not had babies, including men, can have diastasis. Diastasis recti that doesn’t go away after pregnancy or without being pregnant comes down to a pressure management issue, imbalance in our core stabilizing system, and improper function at the areas above (shoulders) and below (hips and pelvis) function that would potentially put excessive load across the abdomen.

What Does Diastasis Recti Feel Like? What Are the Symptoms of Diastasis Recti?

Diastasis recti can cause doming or sinking in along your midline under load (such as sitting up, doing a plank, doing a pull up, etc). This can result in abs that look “pooched” or “still pregnant” and is separate from weight gain, but due to inability to transfer load across the core and/or poor resting tone in abs. The different locations and measurements of a diastasis can vary, depending on what is contributing to the diastasis.

How Can I Tell if I Have Diastasis Recti?

You can do a self-check for diastasis recti by following the simple steps:

- Start by rolling to your side and over to your back. Never sit straight up, always go from your side to put less pressure on your diastasis and PF (pelvic floor). We’re going to check in several places and make notes on this to compare later. The most important thing when measuring is how firm it is when you push down in the middle.

- Halfway between belly button and rib cage Find your belly button and your rib cage. Pick your head up. If you do feel a gap, how wide is this gap? Do your fingers squish in?

- Right above your belly button Pick up your head. Feel here, is there any gapping here? How far do your fingers go down? How many fingers wide is it?

- Below your belly button Pick up your head. Is it met with firmness, or is it soft and squishy?

- Adding in the breath What is your breathing system like? What is your PF is doing? This time I want you to think when you exhale, ribs in and down and PF comes up. What’s your gap like now? Does it get more squishy or more firm? We’re looking for the changes that happen here when you exhale and draw your PF up.

The width and the depth of the diastasis are both important with the width being controlled by rectus abdominis strength and the depth being controlled by transverse abdominis strength with increased focus on improving the depth. Technically anything under 2 fingers wide is not considered a diastasis.

More information on how to tell if you have a diastasis recti can be found here.

What Causes Diastasis Recti?

So then who can get a diastasis recti that doesn’t heal on its own or get one without being pregnant? Diastasis comes down to how you manage pressure in your core. Our core consists of our diaphragm on top, pelvic floor on the bottom, abs that wrap around, and multifidi (tiny back muscles) on the back.

A diastasis can occur when you don’t manage pressure in your core well, resulting in pressure going out through our midline, or an imbalance in pull from our abs, creating a thinning or separation of our linea alba. This will result in poor energy transfer in our system and not ideal support for the rest of our body. This is the most common cause in men and also postpartum women that exercise too hard too soon and make their diastasis worse postpartum.

Diastasis in children is due to abdominal weakness, so there isn’t enough force production to stimulate fascia remodeling in the midline. Most diastasis on children will naturally resolve as they get stronger.

With pregnancy, posture will change to accommodate for a growing belly such that your abs get overly lengthened, diaphragm gets pulled into a flattened and overly lengthened position in the front (affecting how we breathe), back side ribs are compressed (also affecting how we breathe and ab function), and change pelvis position (affecting the resting position of our pelvic floor and abs). These imbalances can create tug of wars between our core and back as well as put abdominals into a position that makes them harder to engage in a balanced way. Many women will recover from the lengthening that occurs postpartum, but some need more help.

Even without pregnancy, individuals can have an anterior pelvic tilt and forward or sideways rib flare that can contribute to these imbalances.

Ideally to control pressure we create a stiffening or corset concept to our core where everything is able to come up, in, around, and together to create stiffness and support to our spine and organs. If you are unable to contain pressure in your system or use a bearing down or pushing strategy for stability, it will leak out through the path of least resistance, resulting in injuries such as a diastasis, hernias, or pelvic organ prolapse.

How to Prevent or Avoid Diastasis Recti?

As stated above, everyone in pregnancy will have some amount of diastasis recti at their due date. The name of the game during pregnancy is minimizing it (without putting your pelvic floor at risk) to help with your recovery postpartum. The more you work on preventing it during pregnancy, the less you’ll have to recover from, but also remember to not exercise too hard too soon postpartum because it’s about a balance in the system and making sure you’re not substituting too much pressure down onto your pelvic floor to minimize your diastasis. Whether pregnant, postpartum, or neither, paying attention to what’s happening at your core when performing exercises will be critical for preventing and correcting a diastasis because you’re only as strong as your weakest link. Check out this article here on how to minimize a diastasis while pregnant.

What to Do about a Diastasis Recti

First, let’s look at the foundations and assess breathing and bracing in isolation. Then you can then take those concepts and build upon them in other movements. For breathing, you are looking for a 360 expansion on your inhale to create balanced length in your expansion to then create a reciprocal 360 compression on your exhale.

Umbrella breathing

Just like any other area of the body, you want full range of motion in the tissue and joints for proper balance in function. Faulty breathing mechanics can result in overly lengthening one area of the core corset (making it harder to shorten and engage for the brace), never lengthening another area (making it be one step ahead on the engagement, creating further imbalances as well as affecting the tissues’ ability to be dynamically strong), and affecting resting tone and position of you abs, pelvic floor, and diaphragm. Think of how a bicep curl is easiest to do from mid range vs trying to curl a weight when your arm is straight or hard to flex when your elbow is already bent. All of this sets up a more challenging bracing strategy which can basically be viewed as an exhale of varied intensity to match the demand of the activity.

Diaphragm movement

Common breathing mistakes

Belly vs chest

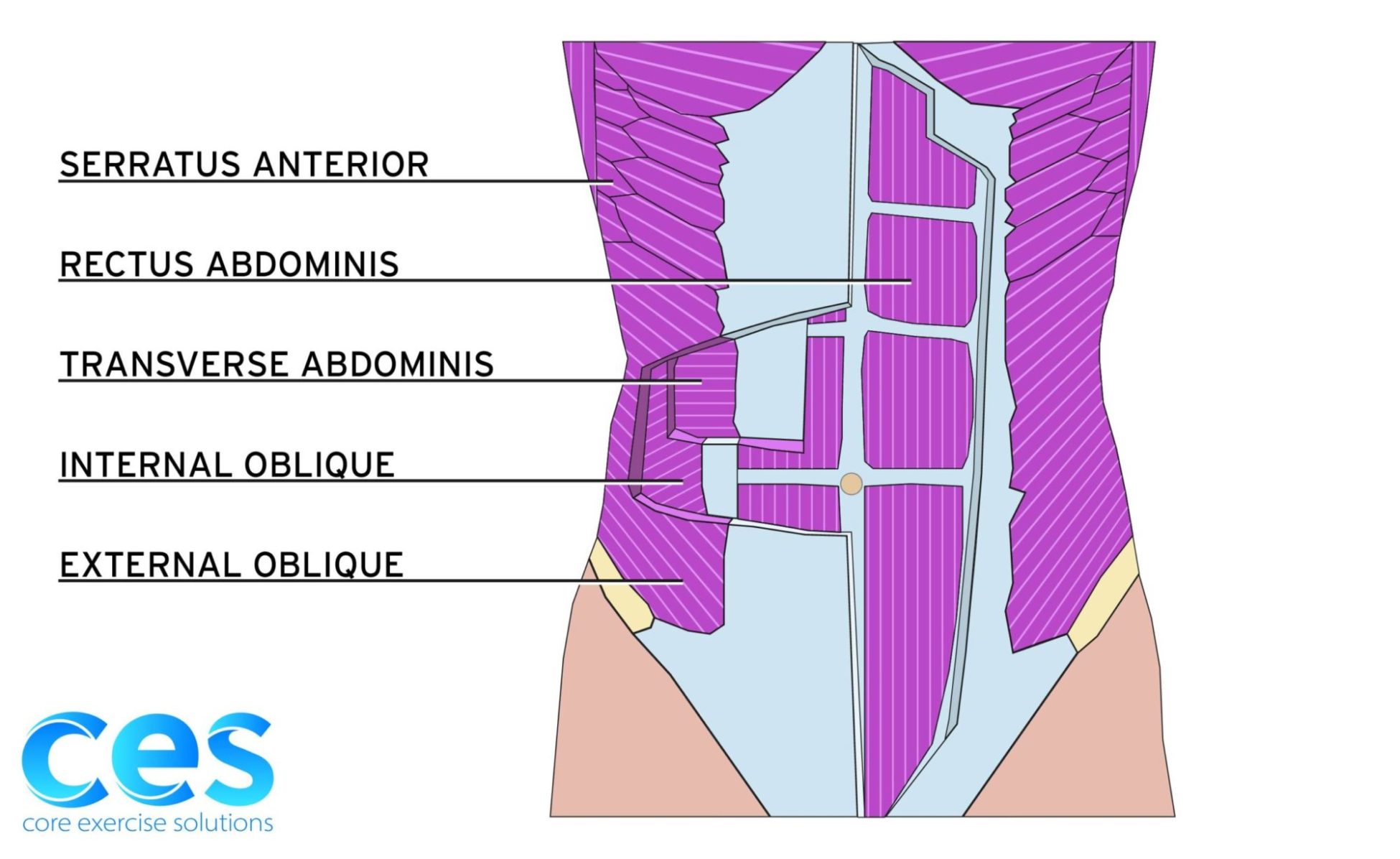

For ab engagement, you are looking for a balance in your bracing strategy, recruiting all of your abdominals equally (from each muscle group to bottom to top) and maintaining that balance in whatever activity that you’re doing to control pressure and provide stability for your body. Our abs consist of different groups of muscles: external obliques that run diagonally from your ribs down toward opposite hip bone, internal obliques that run diagonally in the opposite direction from hip bones up to belly button, rectus abdominis (our 6 pack muscle) that runs run vertically from pubic bone to ribs, and transverse abdominals that run horizontally around our entire core. Then you can break up these muscle groups into lower, middle, and upper portions. You need balance between the different muscle groups and the different levels for a full balanced corset of support and making sure one area isn’t taking on too much load or stress and causing pressure to leak out of the system.

Engage abs equally

If you have imbalance in your TA’s vs rectus, you’ll have a “bread loaf” type of look to your abs, particularly when bracing, and have a diastasis that is deeper since TA’s create the tension across your linea alba and help with load transfer.

Doming

You can also have more dominant lower abs than upper which can coincide with a wide rib cage angle (angle at your ribs as they join together in the front) and a higher diastasis.

External Obliques

You can have a more dominate middle or upper abs, particularly if you are one who has previously used the “drawing your belly button to spine” cue for core engagement or never get rib movement for your breathing, resulting in a cinched in look around your abs and can contribute to more of a lower belly pooch and diastasis at your navel or lower. This can be particularly common for individuals who are group fitness instructors, particularly pilates, where you’re talking a lot and cuing a lot of core engagement, unintentionally being in a state of performing constant reps with shallow breathing as you teach class.

Remember it’s not just about what you do but how you do it. It’s important to check in on what your abs and diastasis are doing in various exercises. Sometimes when put under load a diastasis will improve in it’s measurement compared to the laying down test, which indicates that working the progressive overload in that position will help with your healing. When you don’t progressively overload, the muscles never get stronger and can contribute to a stalled out healing of a diastasis. That being said too, sometimes a movement will be able to be technically performed, but you might have increased doming or squishiness of a diastasis or dominant upper abs resulting in a lower belly pooch that can put pressure down onto a pelvic floor making it vulnerable for injury. These would be exercises to avoid or regress when having a diastasis. This could contribute to doing exercises but not improving a diastasis. Often in the beginning of healing, front loaded exercises are more prone to contributing to a diastasis and are best to be held on until you know you are able to create good tension across your linea alba.

Plank for DR

DR safe exercises

Fascia takes a long time to heal, so it’s about building core strength (through good breathing and bracing strategies) as well as unloading the fascia through good movement patterns and habits that you apply to workouts as well as day to day life and activities. Outside of breathing and bracing, if you are unable to move your hips and shoulders from a stable foundation and independently from your rib cage and spine then every time you you perform a lower or upper body move or squat or reach, you might be putting increased stress and strain on your diastasis which will contribute to the breathing and bracing imbalances and limit the tissue from healing. This can often be the case for someone who has stalled out on their diastasis after working on their breathing and isolated ab engagement.

It’s about taking the foundations that you learned from your breathing and bracing, making sure other parts are moving well so you’re not stealing the movements from elsewhere, and then tying it all together in functional movements.

Making everything a core exercise

How to engage your core correctly

Is it ever too Late to Correct a Diastasis Recti?

It’s never too late! The benefit of working on your diastasis later in life is that you won’t have the effects of newly postpartum hormones that contribute to increase tissue laxity as well as the less than desirable movement and breathing patterns that can occur with taking care of young children (feeding, carrying, holding, etc). Your body is an amazing thing that can respond well to guided movement. You might have old habits that die hard (such as if you’ve been a shallow breather for as long as you remember or had forward head posture since you were 16), but things can still change and improve.

Is Diastasis Recti Surgery a Good Idea?

Often people will view surgery as “the easy route” or once they have surgery they’ll be healed. The surgery itself will help the disruption in the tissue, but it won’t change your breathing, bracing, or movement patterns. Plus, you’ll also have to work through the acute postoperative aspects and tightness that occurs from being “synched up.” That being said, sometimes, despite conservative efforts, someone may still need to have diastasis recti surgery. The more work you put into your body from a musculoskeletal standpoint before surgery, the better outcome you’ll have after surgery. As long as you’re still seeing some progress and having things to work on, consider it as untapped potential for healing.

It’s important to make sure you’ve had the right team and approach to your conservative treatment, remembering that it’s not just about what you do but how you do it, and that getting assistance for release work (in all areas of your body) from a professional can go a long way in the ability for you to engage muscles correctly. Whether surgery is right for you will be made between you, a physical therapist, and a surgeon.

In the end remember that a diastasis recti is a whole body issue, so we need to look at various components to address it. It’s often the victim and not the crime. You can bring some imbalances into your pregnancy that you possibly ignored or were able to get away with before pregnancy (tight hip flexors, shallow breathing, rectus dominance) but were further magnified as you became pregnant. That doesn’t mean that things can’t improve or change, but just consider it as getting multiple bangs for your buck as you work on healing your diastasis by looking at the whole system.

This article was written by Anna Hammond, an amazing Physical Therapist that works at Core Exercise Solutions. You can find out more information about Anna here.

- Mota, P., Pascoal, A.G., Carita, A.I., & Bø, K. (2015). Prevalence and risk factors of diastasis recti abdominis from late pregnancy to 6 months postpartum, and relationship with lumbo-pelvic pain. Manual Therapy, 20(1), 200-205, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2014.09.002

- Sperstad, J. B., Tennfjord, M. K., Hilde, G., Ellström-Engh, M., & Bø, K. (2016). Diastasis recti abdominis during pregnancy and 12 months after childbirth: Prevalence, risk factors and report of lumbopelvic pain. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(17), 1092–1096. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096065

Pelvic Floor and Diastasis: What You Need to Know About Pressure Management

Join us today for this 6-part Pelvic Floor and Diastasis Video Series, absolutely free.

This course is designed for health/wellness professionals, but we encourage anyone interested in learning more about the pelvic floor and diastasis to sign up.

We don't spam or give your information to any third parties. View our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.