Diastasis recti can be a concern for many women during pregnancy. In this article, we’re going to take a look at what percentage of women get diastasis recti during pregnancy, what you can do during pregnancy to decrease it’s severity, and how to boost your recovery postpartum. The abdominal wall being able to stretch to accommodate a baby is an amazing thing!

What is Diastasis Recti?

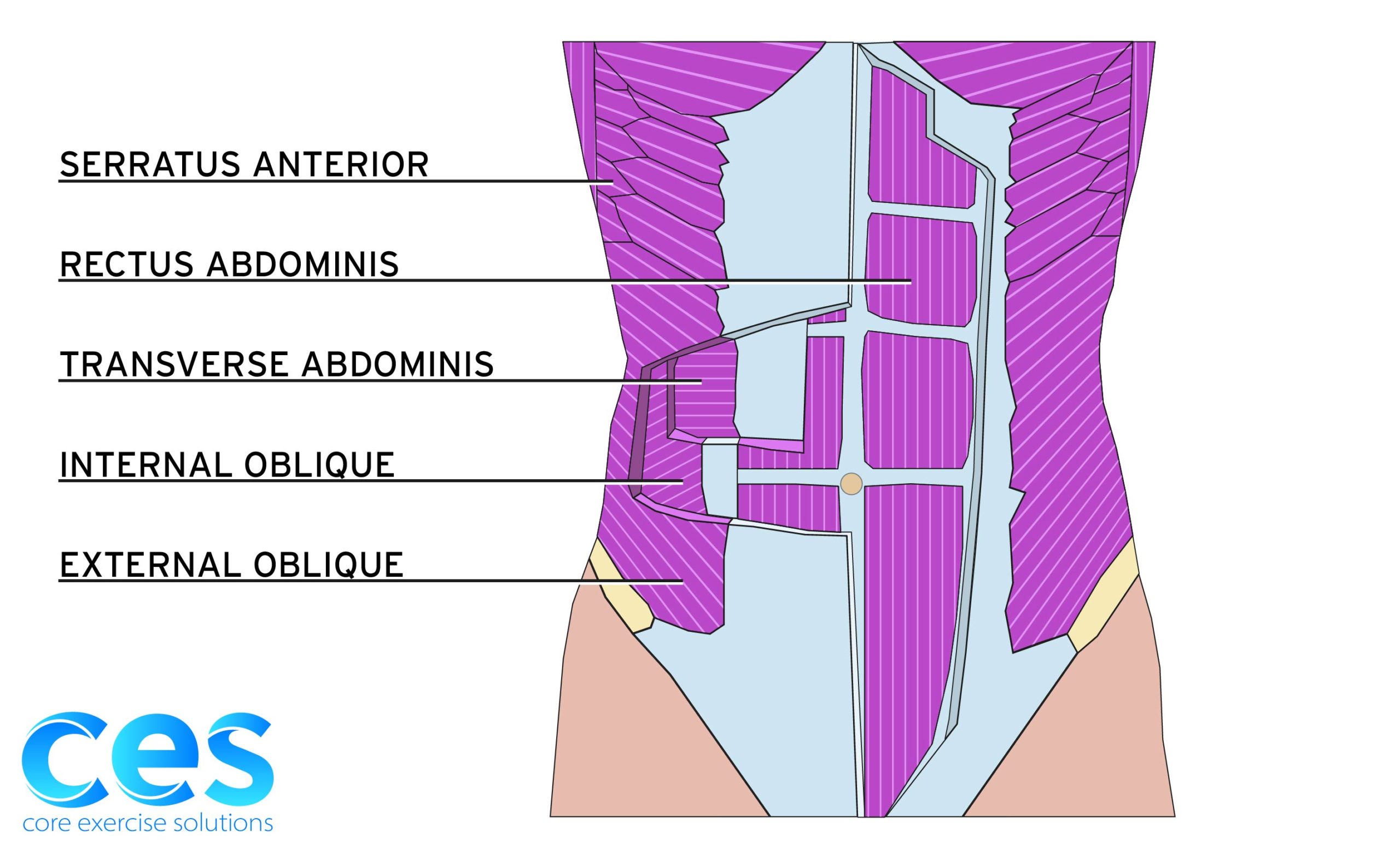

Diastasis recti is the thinning of the linea alba, the connective tissue where your rectus abdominis muscle (six pack ab muscles) meets in the middle. It is made up of the aponeurosis (think saran wrap) that is around the three lateral abdominal muscles -- transverse abdominals, external obliques, and internal obliques. These sheaths encase the rectus abdominis muscle and meet in the midline of the torso.

![Diastasis [Converted] Types of Diastasis Recti](https://www.coreexercisesolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Diastasis-Converted-scaled.jpg)

The fascia can be thinned above the navel, at the navel, below the navel, or its entire length. When testing for diastasis recti after pregnancy, you should measure both the depth and width, at, above, and below the navel.

The location of a diastasis and the corresponding measurements can vary, depending on how your breathing, bracing, and pressure management system works and also how areas above (shoulders) and below (hips) function.

Can you Heal Diastasis Recti While Pregnant?

Some natural stretching and diastasis formation during pregnancy is completely normal to accommodate a growing belly. In fact, according to Mota et al. (2015), 100% of women have a diastasis recti at their due date and 39% have it at 6 months postpartum. Sperstad et al. (2016) stated that 60% of women have diastasis at 6 weeks postpartum. Some women will heal their diastasis on their own while others will need specific exercises to help it heal, and sometimes surgery is needed if the fascia is compromised too much. Diastasis that seem really wide or deep at first, still have the potential to heal, so don’t automatically assume you need surgery.

The goal during pregnancy is to limit the amount of stretch on the midline linea alba to assist in postpartum recovery and help support your body as best you can throughout pregnancy, while acknowledging that you are growing a small human inside and your tissue needs to accommodate that.

The wrong exercises or patterns can cause a diastasis to get worse both during and after pregnancy. Trying to force a closure at your abs can often put extra pressure elsewhere, such as your pelvic floor. That’s why you need to treat the system as a whole, thinking of it as fixing a pressure management system. Everything has to share the load and support, and if you add strength on top of imbalances you’ll just further magnify those imbalances, rather than using the strengthening from corrective exercises to help balance you out. Remember, you’re only as strong as your weakest link.

What Happens to Your Abs and Posture when Pregnant?

When you’re pregnant, your growing belly will stretch out your abdominal fascia, your ribs will flare, and your body will have to accommodate the increased weight in the front. There is also an increase in hormones that contribute to ligament laxity. These help to prepare your pelvis for birth, but they can also contribute to these posture changes. Your body will then have to rely on improved dynamic control by using muscles, or it will create stability through stiffness instead (think constant clenching and feeling tight) or by hanging on joints, ligaments, and muscles at their end range. This can result in an increased sway back posture. This change in posture further stretches out the front of the abdominals while compressing the back. This results in excessive thoracic kyphosis and forward head posture, occasional responsive glute clenching, pressure down onto the pelvic floor, and limitations for the diaphragm to expand, all of which affect how we can breathe and brace.

Simply focusing on not succumbing to pregnancy posture as best as you can will help minimize the postural changes or compensations that occur in pregnancy (and continue into postpartum) as much as is possible. It will also help make sure you’re not putting constant strain on your diastasis throughout the day. When you think about it, 30 minutes of corrective exercise versus the strain of poor posture for the rest of the day -- the rest of the day is going to win.

Here are some main things to focus on. Keep your ribs stacked over your pelvis as best you can, while engaging just enough to support your lower belly. Make sure this engagement is coming from a lift of your lower abs rather than from clenching your glutes. Remember it’s subtle! You shouldn’t be holding a lot of tension. Create length through your spine rather than thrusting out your ribs.

Likewise, avoid pulling your ribs down excessively and having your shoulders come forward, or tightening your upper abs so much that you can’t breathe. Then, know that the strengthening exercises and breathing drills listed below will help give you the tools to achieve the best posture you can throughout your pregnancy.

On average during pregnancy, your rectus stretches out an additional half of its full length. You can think about how unless this is addressed, this would then create more of a stretch across the front parts of your other ab muscles as well. The increased lengthening of your abdominal muscles makes it harder to engage them as pregnancy progresses, resulting in decreased pelvic stability and core support base for your shoulders and hips to move from. Depending on where you carry your baby, postural changes and imbalances you brought into pregnancy can affect what part of your abs get further stretched out, which can impact your ab function and diastasis.

Ab engagement (not only looking at upper, middle, and lower, but also muscle groups) is not created equal -- so it’s important to work on maintaining a balanced ab engagement strategy. This will help with pressure management and determine whether you help or hinder your diastasis with core exercises. The goal during pregnancy is to try and distribute the lengthening in a 360 degree pattern as much as possible, rather than it all going only to the front. This will help take stress off of the linea alba and improve bracing strategies.

Exercises During Pregnancy to Prevent Diastasis

Core Work

When first approaching exercises during pregnancy, it’s important to monitor any bearing down onto your pelvic floor as well as doming in your abdominal wall during the exercise. The goal is to keep exercises and strengthening in your routine for as long as you can safely perform them from a pressure management and bracing strategy standpoint.

Every person will be different when it comes to what exercises they can tolerate throughout pregnancy. It’s important to make sure you’re not doing more harm than good with your exercise while maintaining balance in your system as much as you can.

At some point, because they are more rectus dominant movements, front loaded exercises such as planks, pushups, pull ups and sometimes deadlifts and squats may need to be replaced or modified in your programming, and will usually be modified before other exercises. A pregnant or recovering postpartum abdomen has decreased strength in the TAs which help maintain tension and minimize depth across your linea alba and provide stability to your pelvis and spine. Working on ab exercises that help target the weaker links rather than overloading the rectus will help in maintaining as much abdominal strength balance as you can while you recover postpartum.

Side planks can be turned into a great full body exercise and performed in regressed variations to help meet your body where it’s at, as well as working on breathing under a brace to help with back body expansion. A Pallof press in half kneeling can also be adjusted based on cuing to help target weaker links in your abdominals to create a balanced engagement. It’s about turning every exercise into a core exercise to minimize strain on your growing belly, facilitate balance in your core engagement to minimize doming and diastasis, and acknowledging that the weakest link in the movement may be your core.

Breathing and Mobility Drills

Assessing and optimizing breathing can go a long way toward helping with how you load your core and pelvic floor. Breathing is the foundation for how you brace, and you breathe all day long. During pregnancy, the diaphragm is limited in its ability to expand due to the growing baby progressively pushing up into it and the posture changes that occur due to the increased weight in the front. This posture change creates further length to our abdominal wall in the front and compression in our back, making it harder to breathe into the back and get a good 360 degree expansion of our rib cage and abdominal wall. This creates a “broken umbrella” for your breathing system which will then affect your pressure management

Working on positions where you lengthen your back and compress your front as much as your growing belly tolerates and then inhaling into the areas of restriction can be a great way to maintain back body expansion as much as you can.

Hands and knees breathing is another great exercise to work on breathing in an active way to not only get back body expansion, but also work your abs.

You also lose some thoracic mobility during pregnancy which will create stiffness and length in your TAs and obliques, limiting the ability for them to engage. This can even affect shoulder and hip function.

Your obliques lengthen and contract with thoracic spine rotation (right side external obliques and left side internal obliques will rotate you to the left). External oblique fibers blend with the serratus fibers that help pull the scapula through to assist with reaching across the body and overhead, as well as assisting in the cross body gait pattern (think opposite arm and leg swing) to help with getting weight over to the other leg.

Length to the front parts of your obliques and TAs will contribute to the decreased ability to expand your breath out to the sides and back. This is due to more of the inhale going towards the front to the path of least resistance (which further stretches out your abs) or up into your neck and shoulders.

Working on thoracic extension to help bring mobility to the part of your spine that tends to get more rounded during pregnancy will help with thoracic rotation and also posture. As your belly gets bigger, focusing on tucking your pelvis under, using a foam roller or rolled up towel between your knees, and something under your head for passive or side-lying mid back rotation will help make sure the movement comes from your thoracic spine. Always monitor for doming during any of the movements, stopping the exercise if it occurs.

Upper Body

The serratus is a key muscle to help with scapular positioning and function and neck discomfort, and it also connects our upper body to our core, complementing mid back rotation work. As you go into more forward head posture in reaction to being in more of an anterior pelvic tilt, your shoulders will become more rounded. This makes your pec minor tight and more dominant in function over your serratus and pec major, while also putting your serratus, middle, and lower traps (all key scapular stabilizers and postural muscles) in a more disadvantaged position to function.

Giving a boost to your serratus as well as finding pec major and working on eccentric (controlled lengthening) of your chest muscles will help not only open up your chest, but also to set up your mid back muscles for more success. Lastly, working your lats with your lower traps can help with posture as well as providing stability for your pelvis.

Your core needs to engage well to set a good foundation for shoulder blade function. Particularly during pregnancy, when the abdominal muscles are in a lengthened and disadvantaged position, your core might be the weakest link in loading the upper body. You can modify positions by using half kneeling or a split stance while engaging the hamstring on the front leg to help stabilize your pelvis and create a wider base of support, doing one arm at a time to decrease overall load on your core and pressure management system, or decrease the weight to fit the demands of what your core can handle.

Making sure the movement is being driven by your shoulder blades and not just your humerus (upper arm bone) will help ensure you’re accomplishing strengthening and mobility in your goal areas.

Lower Body

Now let’s look at your pelvis position and hip muscle function. As your pelvis falls further into a tipped forward position, this will not only lengthen your abs but also contribute to decreased glute max and hamstring strength. This can also impact femur position in the socket, further contributing to hip, pelvic floor and core imbalances. Not everyone excessively tips forward. Some women counter the tipping with glute clenching and end up with very tight hip and pelvic floor muscles.

We want to maintain a balance in hip strength (particularly making sure the glute max stays strong) to help ensure your abs do not have to work so hard from being in an overly lengthened position. This will also help keep you from compensating by glute clenching, which can contribute to further hip and core imbalances as well as butt pain.

Doing an exercise like a hamstring bridge (as long as you are cleared by your doctor and can tolerate lying on your back for short periods of time) can be a great way to make sure you can control resting pelvis position. By maintaining good resting length of your hamstrings, you can better access abs and glutes in other hip strengthening exercises such as a squat, hip hinge/deadlift, hip thrusts, bridges, and lunges. You can even perform this exercise in sitting, making sure your ribs stay stacked over your pelvis when you create the tuck-under action at your pelvis.

Once you’ve improved your pelvic positioning, improving femur position in the socket with a variation of iliacus pullbacks and reminding your hip how to extend will help set your glute max up to work.

You can take these isolated movements to your bigger functional movements like squats, hip thrusts, or deadlift/hip hinge. When performing a squat, make sure your movement is initiated through glute length and not by tipping your pelvis forward, and stay grounded through your feet. This will help turn your squat into an ab exercise as well, while also getting optimal glute strength.

As your belly gets bigger, maintaining good core control will become harder, so performing an unloaded squat can help you meet your body where it’s at.

Try This Free Diastasis Recti Educational Series

Dr. Sarah Duvall, PT, DPT, CPT, and the CES Team have helped thousands of women create the strength and stability needed to overcome diastasis recti and build core strength.

Join us today for this 4-part Diastasis Recti Video Series, absolutely free.

We don't spam or give your information to any third parties. View our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

How Long Does it Take for Diastasis Recti to Heal After Pregnancy?

This answer comes down to “it depends”. Pregnancy can expose your muscular cheats and weaknesses that you could maybe get away with before pregnancy. Diastasis recti is also a whole body issue, not just isolated to how our core functions. Sometimes you can improve with addressing breathing and bracing strategies, and other times you have to improve and strengthen how your shoulders and hips function. Either way, working on maintaining a balance of strength in your whole body while optimizing breathing as best you can throughout pregnancy will help you avoid the path of imbalances you’ll need to correct postpartum.

The great news is that it’s never too late to start working on your diastasis. It can even be easier in some ways to do the work when you’re not as newly postpartum and battling ligament laxity from hormones and the challenge of gaining muscle. Plus you’re no longer battling the habits and patterns that occur with baby carrying, baby-wearing, nursing, and the general stress of having young children.

Depending on the individual, some patterns you had before pregnancy that contributed to your diastasis or that you obtained during pregnancy might be more ingrained, so you might have to work longer on them to improve them, but changes and improvements can still happen.

Is it Safe to get Pregnant with Diastasis/Does Diastasis get Worse After Each Pregnancy?

Along these same lines, there is often concern about becoming pregnant while not having fully healed your diastasis. People also wonder if it is safe to get pregnant with a diastasis, or if a diastasis will get worse with each pregnancy.

On the flip side, sometimes women think there’s no point in working on healing postpartum until they are done having children. However, think of it this way -- the better foundation you have to start, the less you’ll have to recover from to get back to a good foundation.

If you start with more imbalances and weaknesses that you did not address, chances are those imbalances and weaknesses will continue to add up and make it a longer road in the end for rewiring patterns and regaining strength. Sometimes the first or second pregnancy might not have been an issue, but the accumulation during multiple pregnancies causes the body to reach a tipping point for further injury. Any time you spend helping your foundation and minimizing the slippage into your postpartum changes will only help you in your recovery.

That being said, if you haven’t healed your diastasis before becoming pregnant, it’s ok! The human body is amazing, and you can accomplish a lot of rehab and strengthening that contribute to a diastasis during those first two trimesters of pregnancy in particular.

Yes, sometimes nausea and increased fatigue can zap our energy or ability to exercise, but even focusing on just the basics of optimizing 360 degree expansion throughout the day and monitoring for strain on your diastasis during daily activities can go a long way. Paying attention to movement patterns and doming during reaching, squatting, and lifting is prevention. Working on better movement patterns is also a sneaky way to gain strength.

Let’s hear from a mama we got the opportunity to work with that came out of her 6th pregnancy better than ever!

The hardest part about pregnancy is the variability of how we feel physically each day, so taking it one day at a time, meeting your body where it’s at, and doing the best you can do that day is what it’s all about. Sometimes you can have a regression during pregnancy due to increased hormones, stress, too much sitting, too much activity, etc. But there is still hope to try and recoup a bit of what you lost during the setback to continue helping your body through your pregnancy.

Remember that diastasis can be a full body issue, from breathing to bracing to pressure management to how our hips and our shoulders function. Every person is different in their recovery, but I hope helping you to understand the foundations and what to look out for will assist you in your healing journey.

Also, know that even though diastasis is normal to have at your due date and some women can heal on their own, you are not alone if your diastasis continues to persist, and there is help out there for you. Going to see a women’s health physical therapist or a fitness expert who specializes in pregnancy and postpartum training can help you get the most out of the effort you put into healing and achieve the success that you deserve.

This article was written by Anna Hammond, an amazing Physical Therapist that works at Core Exercise Solutions. You can find out more information about Anna here.

References:

- Mota, P., Pascoal, A.G., Carita, A.I., & Bø, K. (2015). Prevalence and risk factors of diastasis recti abdominis from late pregnancy to 6 months postpartum, and relationship with lumbo-pelvic pain. Manual Therapy, 20(1), 200-205, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2014.09.002

- Sperstad, J. B., Tennfjord, M. K., Hilde, G., Ellström-Engh, M., & Bø, K. (2016). Diastasis recti abdominis during pregnancy and 12 months after childbirth: Prevalence, risk factors and report of lumbopelvic pain. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(17), 1092–1096. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096065

If you are interested in reading more about diastasis, check out these articles!

Pelvic Floor and Diastasis: What You Need to Know About Pressure Management

Join us today for this 6-part Pelvic Floor and Diastasis Video Series, absolutely free.

This course is designed for health/wellness professionals, but we encourage anyone interested in learning more about the pelvic floor and diastasis to sign up.

We don't spam or give your information to any third parties. View our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.