Breathing and addressing how we breathe has become a popular topic, for good reason. Great breathing can make the difference between having a super strong, fluid, pain-free body, or one that's under constant cortisol distress, locked down by tightness, and with decreased core control. It can also have a dramatic effect on healing a diastasis recti and pelvic floor dysfunction.

You might have heard that shallow breathing is bad and diaphragmatic breathing is good, and so you started letting your belly expand with every breath.

Well, not so fast. I’m not saying that belly breathing is always bad—but let me take you through some reasons why it's not optimal, and what you should be doing instead.

Keep in mind that making these changes may need to happen in stages and specifics can vary a bit, depending on the individual. As you bring awareness to deep versus shallow, belly breathing at this stage can be a good first step. You can't fix everything at once, and going down instead of up with your breath is better! If you tend to constantly hold in your abs or have lateral ab tightness, cueing to inhale into your belly might help.

However, belly breathing alone doesn’t include the full mechanics for optimal breathing, so it can affect how your core functions as well as contribute to back and neck tightness.

Once you’ve developed awareness for sending your breath down, then it's time to refine it into more of a 360 degree approach so you’re not getting only belly movement with each breath.

What are the Benefits of Using Proper Diaphragmatic Belly Breathing?

People often think they are doing diaphragmatic breathing, when in fact, they are only breathing into their stomach. But your lungs aren’t in your stomach, so if you’re just moving your belly when you breathe, you’re not actually getting full expansion and deflation of your lungs. This can lead to a protruding belly and affect the healing of a diastasis and pelvic floor function. So let’s talk a bit about proper breathing techniques and why 360 degree breathing is so great.

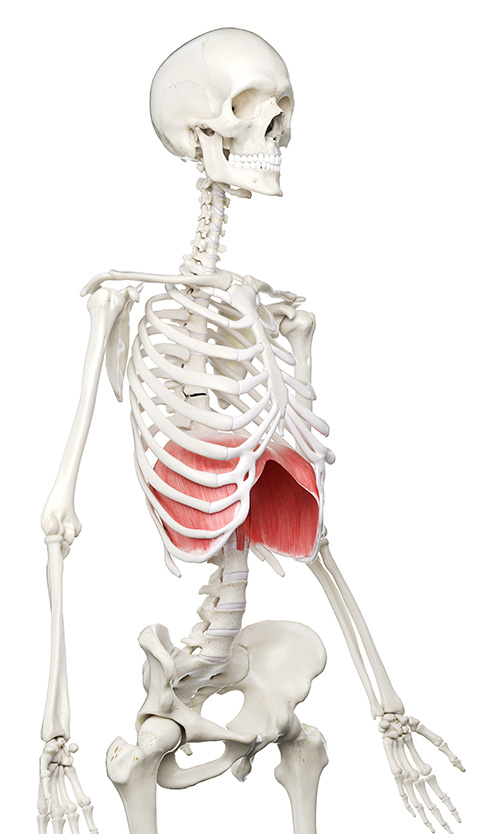

The diaphragm is the primary muscle of inhalation. When you take a deep breath in, your diaphragm contracts down. This pulls your rib cage open to bring air into your lungs. Your diaphragm gently pushes down into your organs, which then expands your belly, sides, and back, and lengthens your pelvic floor. The exhale should then be a natural recoil of this stretch, allowing the organs to go back up into our thoracic cavity, the diaphragm to lift, and the rib cage to compress, which sets everything up for the next inhalation.

Diaphragm and Pelvic Floor Movement Video

From a muscular standpoint, intentional breathing drills can improve postural support, decrease back pain, and further improve breathing mechanics. (Boyle et al., 2010). You can use breathing to release muscular tension by creating length to the muscles from the inside out. By sending more of the breath into your back, you’re not only helping to release your back muscles, but also decreasing the amount that your abs are lengthening in the front to improve postural support, diaphragm positioning, and breathing mechanics.

Breathing is the foundation for how we manage pressure and stabilize ourselves. Sending more breath into your abs instead of your back can lead to lengthened abs and shortened back muscles, which affects core stability. If you tend to inhale up, then the exhale will push pressure down, contributing to increased stress on our pelvic floor and diastasis. Getting an inhale to go down and out helps us to use our diaphragm, and this also sends the pressure back up and in when we exhale to support our core and pelvic floor.

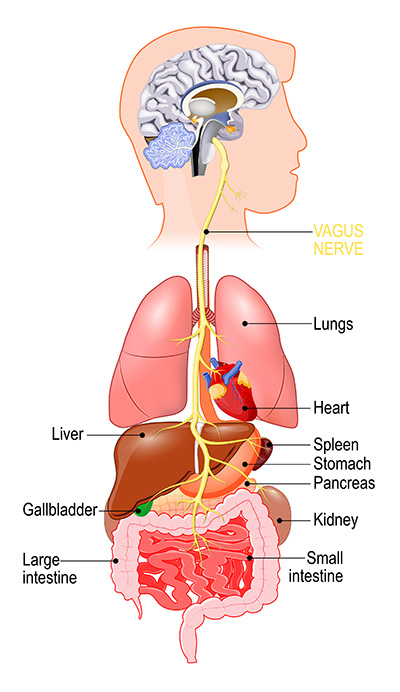

This great movement of the diaphragm even has an effect on the nervous system. The vagus nerve runs through the middle of our diaphragm. (Bordoni et al., 2013) It is part of our parasympathetic nervous system and facilitates resting, relaxing, and digesting. Diaphragmatic movement stimulates the vagus nerve, and this sends a message to the brain, telling you to relax. Research even shows that making your exhales twice as long as your inhales can be more beneficial to the nervous system than meditation! (Balban et al., 2023) Lots of wonderful things happen when we relax. We have a decreased fight or flight response that results in sleeping better, pooping more easily, less pain, better sex, and better digestion. Win-win, all around.

It can then be a bit of “the chicken and the egg.” Do we go into a shallow breathing pattern because we are in a sympathetic state, or does our shallow breathing pattern contribute to the sympathetic state? It’s not that we don’t want to be able to utilize that state when needed, but if we’re always living there, we have nowhere to ramp up into and we can get worn down.

No one needs that extra stress! Life is hard enough, so let's break it down a bit more and get you into a better deep breathing pattern.

Along those same lines, let’s make sure that breathing drills don’t stress you out! You don’t want to force breathing because this can create increased tension and stress. As you work through these drills, aim for a “3 out of 10” effort that is slow and steady, and no one would be able to hear you breathing on either the inhale or the exhale.

Assessing Your Breathing

Now we’ll get into three steps to start this journey of improving your breathing.

Step #1: Improve Your Awareness

You can’t change something you aren’t aware of, so the first step to proper breathing is bringing awareness to what you are doing.

How much stomach movement should happen when we breathe?

Correct breathing is not as simple as breathing into your stomach and making your belly rise and fall. It’s also not about which is better: chest or belly breathing.

Sure, belly breathing is more preferable than breathing up into your shoulders, but too much belly movement can prevent your abdominal separation from healing and may cause back pain, hip pain, and core instability.

When you take in a breath of air, you should see your chest expand (that is where your lungs are located, after all!) and your ribs should move out to the sides. If your chest or back are tight, this expansion is difficult. Our bodies naturally follow the path of least resistance, so chest or back tightness can force pressure up into your neck and shoulders. Or, if you are able to send the breath down but your abs are weak, then your belly says, "I can easily expand without any effort. Who needs core control, anyhow?" This excessive lengthening of your abdominals can further contribute to chest and back tightness.

Check out this video for chest versus belly breathing visuals.

Do your ribs expand out in a 360 degree, umbrella fashion when you breathe?

Place your hands around the bottom of your rib cage and take in a big breath of air, then exhale out. Your ribs should move out in the front, sides, and back, and then come back in on the exhale in a 360 pattern. Did you feel them move? They should move a lot! Maybe you only felt some of your ribs move? Did the ribs on the back right side under your thumb move as much as the left side? No? Then maybe you found the source of that neck or mid back tightness you've been feeling. Fascinating, isn't it?

Correct Breathing Diaphragm and Rib Cage Movement

Does your diaphragm drive the rib cage movement?

Repeat the above experiment, but now place your hands just below your ribs. Did you feel expansion right under your rib cage, or did your rib cage move due to your belly sucking in and shoulders shrugging up? You want to feel the area just below your ribs push out as your ribs expand. This indicates that your diaphragm is contracting down to expand the ribs, rather than sucking it up as the ribs pull out.

Sucking the diaphragm up when pulling the ribs out or constantly holding tension in your abs could be a source of that neck tightness you’ve been feeling.

Neck Tightness: Check Your Breathing

To correct this, you might feel like you need to breathe into your belly and sides to help get the diaphragm to pull down. This might be easier to do in certain positions than others, and you might also need to work on rib cage mobility to improve the position of your diaphragm for it to then pull down from.

Step #2: Improve rib cage mobility and intercostal strength for better breathing mechanics

Now that you are aware of the patterns we’re striving for, let’s help make it easier. Proper breathing takes good rib cage mobility, intercostal strength, and core strength, and even postural components can affect it. It isn’t just about the inhalation, but the exhalation as well.

Weak intercostals and a rigid rib cage (which is very common after pregnancy) can affect both our inhales and exhales. As we breathe, think of the individual ribs as little fingers that we want to spread apart and close back together. This allows for a relative movement within the rib cage, changing its shape, rather than just a change of orientation (where the same shape is maintained while the rib cage tips or rises up and down as one unit).

When it comes to rib cage mobility, think of the rib cage as a water bottle with dents in it. You’ll choose props and positions to help expand out the dents and compress where it’s too expanded. This will help both the inhale and the exhale, improving intercostal strength and your diaphragm and pelvic floor movement, and also help to downregulate how much you need to use your abs and accessory breathing muscles to move your ribs.

Child’s Pose Breathing

Rib Cage Smash

*If you have osteoporosis or osteopenia, please consult a healthcare provider before trying these exercises.

Unsticking the scapula from the rib cage also helps to improve rib cage mobility and resting core tension. If the scapula can’t move freely over the rib cage, you might be getting more movement in your spine than in your scapula as you reach and pull, which further lengthens your abs.

Unstick the Scapula

Oftentimes, people will complain of not being able to get in enough air. Part of this could be due to not expanding all aspects of the rib cage and core canister (which happens when you breathe only into your belly).

If your ribs can’t expand on the inhale, then you’re likely to get more expansion into the belly or up into the neck and shoulders. Remember that if the inhale goes up, then the exhale goes down, which we don’t want. We need that nice length and 360 degree expansion to give the abs and ribs good positioning to come back in from on the exhale. If you never expand, then you’re just going to further compress what’s already tight. This can put more pressure down onto the pelvic floor and lower abs.

Alternatively, it could be that you’re not getting a full exhale. You might have ribs that stay wider, a diaphragm that stays descended in a more inhalation state (resulting in the use of accessory breathing muscles to help with the inhale), or the tendency to over-recruit your abs to pull the ribs down. This can contribute to ab gripping and an imbalance of pressure out into the abs or down into the pelvic floor, which can then affect our core strength, pelvic and spinal stability, diastasis healing, and pelvic floor function. A rib cage that is able to fully compress and strong intercostals help to return the diaphragm and pelvic floor to a lifted state, and this allows the diaphragm to be in a good position to contract back down and facilitate the inhale.

Step #3: Strengthen Your Abs

Breathing and core strengthening feed off each other. Not only does back-body expansion and rib cage mobility help by increasing the ability to expand into paths of more resistance, a strong core also helps increase the path of resistance for your abs. Without that resistance for your core, your rib cage doesn't need to expand to get in air, so it only expands in the front. That lengthens the rectus and a lot of fascial connections while keeping your back and sides tight. No wonder so many people end up with an abdominal separation that won't heal! Belly breathing expands right into that separation, so it never gets a chance to improve.

If your core isn’t strong, you’ll use your diaphragm and psoas to help stabilize your spine. (Siccardi et al., 2020) This prevents the diaphragm from working as efficiently for breathing mechanics and can contribute to back tightness.

Without decreasing the resistance in stickier parts of your rib cage before adding in a brace, you’re in a sense creating double compression and an all-or-nothing type of contraction. It can feel like you can’t breathe when bracing or an over-recruitment of the abs, and it may contribute to a shallow breathing pattern.

If you don’t follow up rib cage mobility work with core work, then your back will just go back to being tight. Working both helps prevent your belly from going straight out with each breath and creates more of a 360 degree breathing pattern.

If you get the correct expansion of your entire abdominal wall, you will be able to maintain some core tension throughout an exercise while breathing for both the inhale and exhale, taking your core work to a whole new level. This is particularly helpful with any lifting and carrying. (It’s not like you can hold your breath the entire time you’re holding your kid!)

Hands and Knees Breathing With Hamstrings

Side Plank With Balloon

**Side Note: If you have prolapse or a hernia, you need to make sure your core and pelvic floor is timed with your diaphragm and firing correctly before attempting any deep breathing with a balloon. If done incorrectly, it can make your symptoms worse.

Translating Breathing to Function

Without this tension and proper expansion on the inhale, it will be challenging to sustain core tension to perform loaded movement, which can lead to decreased spinal and pelvic stability. Poor lumbopelvic stability contributes to feeling tightness or pain in your piriformis, hamstrings, SI joint, or low back after movements like squats and deadlifts. The psoas and diaphragm will increase their work as postural stabilizers, which can also affect hip function. Because the diaphragm will be too busy working as a primary stabilizer, it can also affect breathing mechanics and create a negative feedback loop in the system.

There is a time and place for proper breath-holding (such as when maxing out your deadlift), but if you are suffering from back or neck tightness, hernias, abdominal separation, or pelvic floor issues, you really need to take a closer look at how you manage pressure in your core and why misutilization of pressure is causing issues.

Working on some of these connections in isolation can help you continue these ideas into other movements. This carryover can help improve not only your breathing, but also your mobility.

Improve Thoracic Rotation With Upper Body Strengthening

Remember that improving breathing can happen in stages, and there will be some ebbs and flows to your abilities, depending on stress and tightness in your body. It won’t always need to be an extreme emphasis on movement patterns or the amount of movement, but having some extra emphasis in the beginning helps to recalibrate our patterns so that in the end, it becomes second nature. The goal is no matter how quickly or deeply you breathe, you still get a general 360 degree movement pattern, sending the inhales down and then your exhales come back up.

Research:

- Bordoni B, Zanier E. Anatomic connections of the diaphragm: influence of respiration on the body system. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013 Jul 25;6:281-91. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S45443. PMID: 23940419; PMCID: PMC3731110.

- Boyle KL, Olinick J, Lewis C. The value of blowing up a balloon. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2010 Sep;5(3):179-88. PMID: 21589673; PMCID: PMC2971640.

- Balban MY, Neri E, Kogon MM, Weed L, Nouriani B, Jo B, Holl G, Zeitzer JM, Spiegel D, Huberman AD. Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. Cell Rep Med. 2023 Jan 17;4(1):100895. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100895. Epub 2023 Jan 10. PMID: 36630953; PMCID: PMC9873947.

- Siccardi MA, Tariq MA, Valle C. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Psoas Major. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL); 2020. PMID: 30571039.

Free Pelvic Floor Educational Series

Dr. Sarah Duvall, PT, DPT, CPT and the CES Team have helped thousands of women create the strength and stability needed to overcome common and not-so-common pelvic floor issues.

Join us today for this 4-part Pelvic Floor Video Series, absolutely free.

We don't spam or give your information to any third parties. View our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

Working with pregnant and postpartum clients/patients?

This 6-part course offers key takeaways on breathing, pelvic floor strengthening and diastasis recovery. Sign up and start learning today!