You may have taken the plunge to start thinking about your feet, read or heard some about barefoot running, or maybe you’ve simply gotten used to pandemic life of no shoes and are asking yourself, “can I work out barefoot?”

The benefits of exercising without shoes

Being able to stack our ribs over our pelvis is critical for creating a strong foundation for our body to move from. That being said, awareness of how our feet interact and touch the ground can also play a huge role; not only with what happens at the lower leg, but also up the chain. Whether you have a history of shin splints, plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendonitis, or even hip or knee problems, taking the foot and ankle into consideration (not only in isolation, but in connection with the rest of the body) can go a long way.

More professionals are encouraging individuals to do workouts, or at least warmups, in no shoes or minimalist shoes. Studies have shown that people with a history of ankle sprains have decreased activity of their glutes and an increased risk of hamstring strains, and not healing a sprain can potentially lead to chronic ankle sprains and instability. So it goes to show that paying some attention to that old ankle sprain (or multiple sprains that you disregarded) could be something to consider for untapped potential in your whole body. Some of you may have already explored arch strengthening exercises, but how about taking it a step further so you’re connecting with your feet through bigger movements to continue the strengthening and positive effects up into the knees, hips, and even upper body?

Things to consider

We don’t necessarily want to stay bolstered up in orthotic support forever, because it’s important for all our body parts to be able to move in all directions and under control. However, we have to “earn” the right to do that. Lower body injury rates went up with running after the publishing of the book Born to Run (about barefoot running). This is not to say that barefoot running doesn’t have some good ideas behind it, but many people were going from being completely shod in cushiony, motion-controlled shoes straight to naked feet with no change in their amount of running, addressing of running form, or strengthening the entire lower body and core to make sure their muscles could handle the absorption and control that was previously done by shoes. This led to overuse injuries such as -itis’s of the lower body and stress fractures, which often result from doing too much, too fast, too soon with the whole kinetic chain of the body not doing its part.

If the arches of your feet are hurting during exercise or you have some form of foot or ankle injury, going barefoot might be too much for your body at the moment. As mentioned above, you need to find out if your foot and arch are to blame or if it is caused by something higher up the chain. Control and positioning of the pelvis and femur from glute, lower ab, and adductor weakness can have a trickle-down effect to the foot, resulting in compensations that put extra stress through tissues that are not built to handle the load (particularly if it’s a chronic condition like plantar fasciitis or Achilles tendonitis). So it’s important to make sure you’re addressing what’s happening there as you unload the tissue at the foot and ankle, taking this time to give the foot and ankle some extra support through orthotics, more supportive shoes, or a heel wedge. Then it’s about progressively reloading the tissue to help remodel and re-educate it on its role, and looking at how setting up and addressing the foot can also help set up the hips for balanced strength.

How to do barefoot workouts

I highly recommend exploring your arches through some of Gary Ward’s programs, What the Foot or Waking Up Your Feet. If you haven’t heard of him, How to Build Arch Strength will introduce you to the concept of connecting to and strengthening your arches. Here I’ll go through how to apply that in other lifts as well so you can take those concepts to bigger movements not only to further benefit your arches, but also to continue the goodness up the chain. I encourage you to check out the Waking Up Arches and Big Toe Movement drills to help you connect to those areas before adding more moving parts for optimal barefoot training.

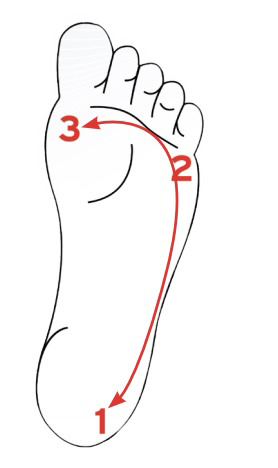

Just like in the waking up arches or big toe exercises, when your entire foot is on the ground during a movement, you’re looking to maintain equal contact between the base of your big toe, pinky toe, and the back of your heel throughout the entire movement.

Bringing this focused attention and awareness to your foot will change how you load your pelvis and hips. To begin, you can simply start with a good tripod foot (you may need to reach down and pull your toes apart rather than have them all scrunched together) and pay attention to whether you’re able to keep that contact through your entire foot as you lower down. Your weight might shift off the back of your heels, or your toes might pop up. Simply see how it feels to try keeping the back of your heels heavy as you lower down into the movement (as if there were a hundred dollar bill under your heel that you wouldn’t want me to take at any time during the movement) and resist the urge to let your big toes pop up. Your big toes lifting through fascial connections will encourage more hip flexor action, whereas keeping them down will help connect to your arches, deep core, and glutes. Sometimes this is easier said than done and we may need to break down components of the bigger movement to make it easier, looking not only at the foot, but also the pelvis and even upper body. That being said, more often than not you can still use this as a great starting point to dabble into the benefits of finding a grounded foot during movement, and good intentions can go a long way.

Let’s take it a step further, looking at your arch being a bit more dynamic. In a squat or a split squat, as you lower down into the movement, you’re doing the beginning movement of the Waking Up Arches drill. Your heel is staying heavy, while your knee goes forward over the midfoot, taking you into ankle dorsiflexion range through controlled lengthening of your calf muscle. Your arch pronates as you let it collapse and your toes splay, which helps with maintaining pelvic stability and eccentric glute lengthening. When you come back out of the movement, your arch will lift and re-engage as you press your big toe down (creating a short foot) as you then drive through your heel to create a strong foundation for your foot and hips to press the floor away. Often a hip thrust movement is encouraged, but this actually makes the femur shove forward in the socket or causes the upper body to lean back compared to your pelvis. The concept of being grounded through your entire foot and pushing straight up might feel like less movement, but it will help maintain a good, stacked position for your rib cage over your pelvis and maintain balance in your hips. Just like in Waking Up Arches, if you’re having a hard time doing this, don’t be afraid to use supports and wedges so your body has something to “feel.” If your foot isn’t mobile or strong enough, not using the wedges will be too challenging and defeat the purpose. On the flip side, if you never stimulate it by making the exercise slightly challenging, then your feet can continue to stay asleep and full of untapped potential.

You can give your glutes a boost in a squat, bridge, or hip thrust by thinking about finding your arch or big toe and feeling the inside of your heel (you can put a sock under your arch to find and connect with it, or a wedge under the outside of your heel to tip you toward your arch) as you then push your knees out (using hip external rotation) to kick more glute med and max into the equation.

In a hip hinge or deadlift you’re not going to use as much ankle dorsiflexion range of motion, so the movement won’t be as dramatic as the squat or lunge, but you can still think about the general mechanics of finding the arch and big toe as you lower down and then press your big toe down and find your heel as you push back up.

For the upper body, because you’re not dynamically moving through your foot, you can simply apply the “short foot” concept to tap into your deep core stabilizing system through fascial slings to create a great foundation to drive from in your upper body.

The higher the intensity, speed, degree of movement (such as including a plantar flexion or a calf raise in the movement) or volume that you do (such as thinking of it as reps/steps in a mile rather than “just a mile”), the more demand it will take out of your muscles. This is where you want to build up to more of a minimalist shoe, using static lifting and isolated arch and ankle work time done in minimalist or barefoot shoes, but then allow yourself to have a bit more support and cushion in the higher level or higher volume activities to meet your body where it’s at and help make sure you don’t overstress tissues and cause an injury. Going barefoot when your tissue isn’t ready for it is just like going from lifting ten pounds in a squat to five hundred without progressively working up to it. It just isn’t going to end well! Which shoe works well for you will depend on you as an individual, and can change as your body changes. Making sure you have proper support from your hips and core during movement will also help your poor feet avoid taking on extra load than what they are built for, as will using good form and technique for higher level activities (just because you are able to do something doesn’t mean it’s a good way of doing it). So be sure to train wisely, and listen to your body for the first signs of, “I’m not so happy about this,” starting as a whisper rather than waiting for your body to scream at you to listen and then having to take time off to fix an injured body. Just because “some” is good, doesn’t mean “more” is always better.

Even if you can’t exercise without shoes due to gym rules or location, bringing awareness and these concepts to wearing shoes that have a wide toe box, zero drop, and minimal toe spring can be great for helping your feet do what they’re supposed to do versus being trapped in a confined space and never being aware of the connection to the ground or having the freedom to do their job.

You can apply wedges as described above to assist in optimal function as your foot and ankle mobility catch up, or use an incline for your heels to accommodate a lack of ankle dorsiflexion range of motion. The theoretical end goal would be to train your foot and ankle (as well as pelvis) independently a little bit each session, and then tie it all in together so you can eventually wean away from additional supports and be your strongest from the bottom up.