When people report feeling their lower back in a squat or deadlift, they often think it’s because their back is weak and it needs to get stronger. In reality, it means that they have lost pelvic control and positioning of their rib cage over their pelvis. This can happen for different reasons, including the inability to load leg muscles (particularly eccentrically, under control) or stabilize the pelvis with lower abs, a lack of isometric strength in scapular stabilizers, joint limitations, and balance from one side to the other. The challenge with troubleshooting a squat is that it takes multiple joints through a large range of motion, all at once, with each part playing an important role. It is a full body exercise where you might be able to make the movement happen, but by what means, and at what cost? If one area isn’t doing its job, then the motion will have to come from somewhere else. Let’s break it down a bit to see where the trouble may lie.

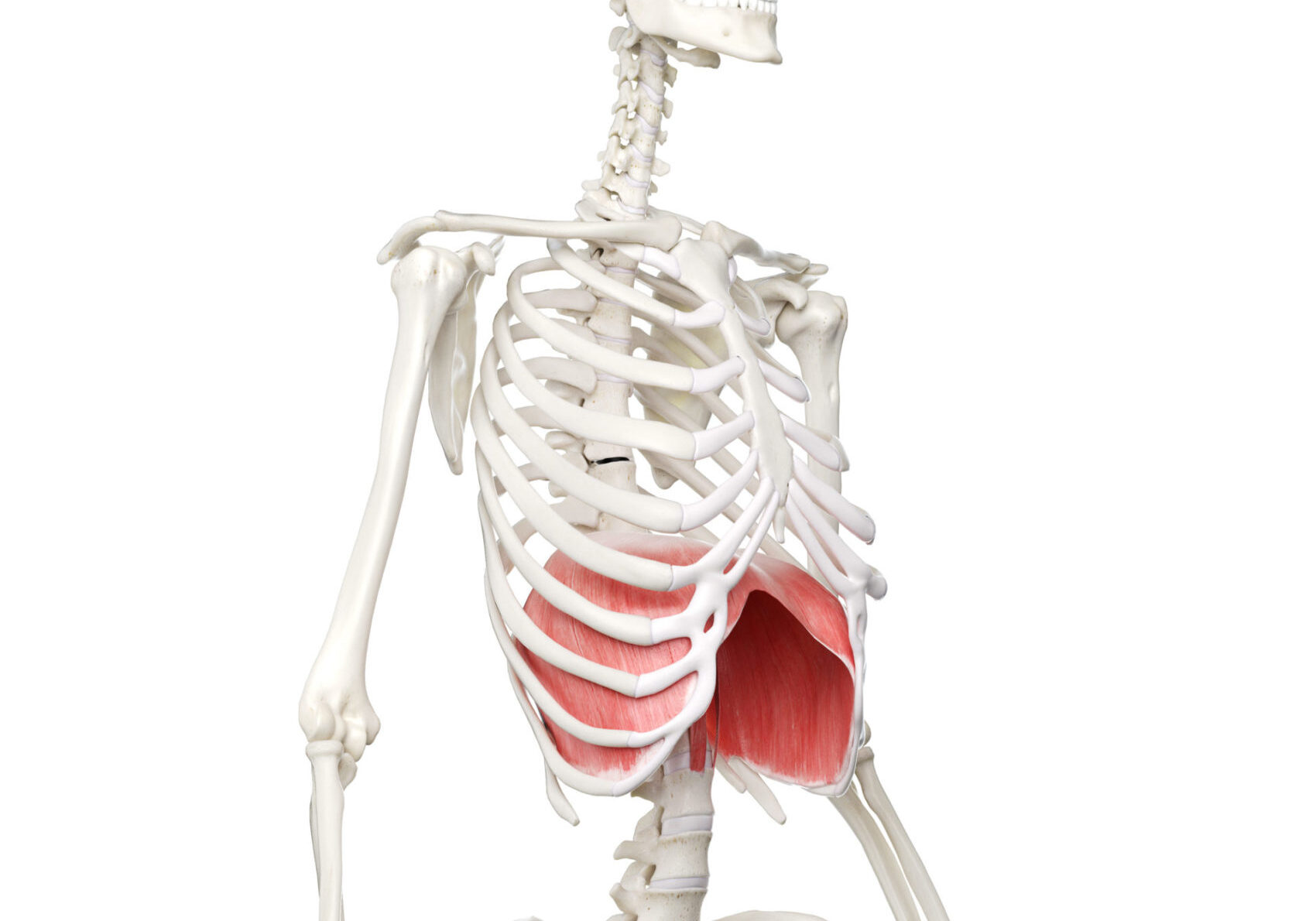

The core muscles stabilize and protect the spine

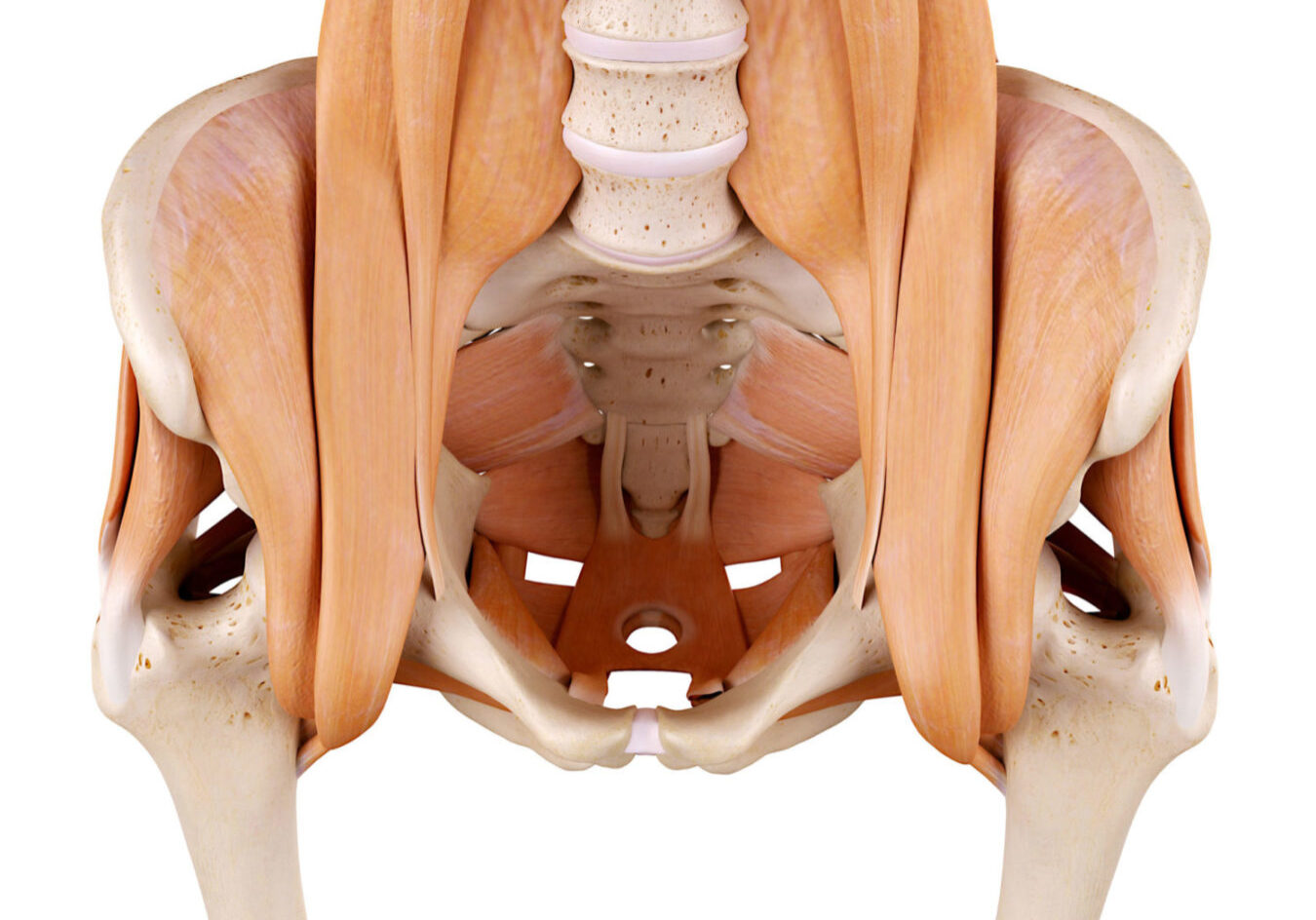

This is an important component for setting a strong foundation to drive the movement. Without this stabilization, it’s like trying to build a house on quicksand. Your core is not only your abdominal wall, but it is actually a canister that includes your diaphragm on top, pelvic floor on the bottom, abdominals (which connect the ribs and pelvis, and wrap around to our back), and multifidi in the back. Multifidi are not often discussed much, but they are tiny muscles on either side of the spine that work on precise segmental control, working together with your lower transverse abdominals and pelvic floor to help create pelvic stability.

LET'S LOOK AT VARIOUS COMPONENTS THAT CAN AFFECT HOW WE ACCESS OUR CORE:

1. Proper breathing

What does your breathing look like?

The diaphragm is the driving muscle behind the action of the canister and your breathing and bracing system. Your diaphragm and external intercostals are the only active muscles of breathing at rest. The diaphragm pulls down and contracts to widen the rib cage (both forward and back, as well as to the sides for 360 degree expansion), gently pushing down onto your organs which distend outward and down. This eccentrically lengthens the abdominal wall and pelvic floor, and provides stability for the spine through expansion. As your lungs then fill up with air, there is a 360 degree expansion in the upper chest wall and ribs as well.

On a relaxed exhale, everything pulls back up, in, and together -- lifting the pelvic floor and diaphragm back up. The abs and ribs come back in again in a 360 degree compression, creating a full, supportive containment of the canister to stabilize your spine. Getting this system working well builds a great foundation for when you increase intensity and bring in more active ab or pelvic floor engagement to meet the demand of your activity. If you have poor breathing mechanics and habits, then you are just adding strength on top of dysfunction -- but you don’t need to have a perfect breathing system in place before advancing your exercises. Moving forward with good intentions while continuing to connect and chip away at breathing will serve you well, and working on strength imbalances in your body will continue to help with your breathing.

2. How to breathe during squats

Can you maintain the good breathing pattern of a 360 degree inhale under load (eccentrically loading your canister)?

Or do you fall into the all-or-nothing brace strategy where you are either over-flexing your abdominals and slipping into a shallow breathing pattern, or losing all sense of a brace as you breathe? This will not be an efficient or sustainable system, so something will eventually fail. You are making certain parts of your body do more work than what they are built to do, while other parts are on vacation. Our body likes to move as efficiently as possible. Being able to breathe under a brace will also help strengthen your abdominal muscles in a greater range of motion vs only in an isometric position (think bicep curl, being able to go through full range or only pulsing at the top).

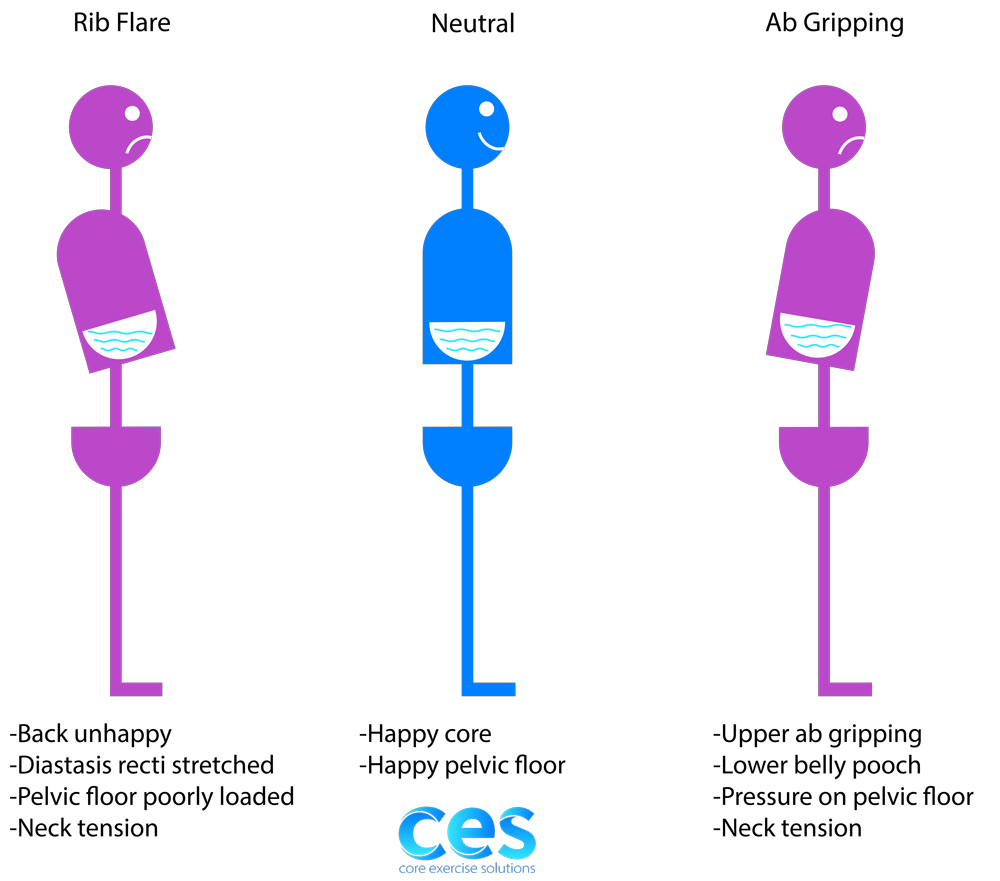

3. Stabilize your squats with good rib cage and pelvis positioning

Can you maintain a good rib cage over pelvis positioning and brace while finding your scapular muscles and hip muscles?

Poor rib cage positioning over the pelvis will affect the resting position of your core canister, how well you can breathe and brace, and your ability to maintain good pelvic stability. If you lose your positioning, it changes muscle length tension relationships throughout the body and affects how you’re lengthening or contracting through muscles and joints elsewhere. Specifically at the lumbar spine, both falling into an anterior pelvic tilt (resulting in excessive lumbar extension and spinal compression) or posterior pelvic tilt (resulting in excessive lumbar flexion and paraspinal and vertebral disc strain) can occur as compensations from the loss of pelvic stability, resulting in poor eccentric glute lengthening and low back pain. We are only as strong as our weakest link.

4. Check head and neck positioning when squatting

What are your head and neck doing?

Everything matters, from head to toe. Movement in your spine at one section affects the position of your spine elsewhere. This also impacts the role of fascial lines on our system (from Thomas Meyer). Positioning or tension in one area can change the position or tension in another area. A common cue is to look up with your neck (people often tend to do this when something gets challenging). The goal for this is to improve scapular positioning, but often the scapular position won’t actually change and only the neck moves. You might lift your chin and just extend the upper cervical spine, disconnecting your deep core front line, resulting in a matching overextension of the lumbar spine. This results in overuse of paraspinals and extensors, as well as using your facet joints to lock in stability through positioning at end range instead of stabilizing with muscular control and balance between both the front and back of your spinal stabilizers. This all contributes to changing the rib cage over pelvis positioning and alignment, and affects both upper and lower body function.

Try it out

To explore this, play with your head position by lifting your chin and looking up while doing a squat. Then try the movement as if someone were pulling your hair from the top of your head throughout the movement. I’m not asking you to chin tuck, but instead, grow taller through your spine. You can even pull the middle of your tongue back on the roof of your mouth to help with this. Go slowly, so you can truly feel it, and make sure you don’t lose that length in your neck. Did you feel a difference?

Yes, it can be harder to do at first, because it exposes your weakest link and deep core rather than using the superficial muscles -- but sometimes this can give you a boost of power or increased ease of activity. Either way, discovering and working on your weak points will help you use the right muscles and improve your strength for the long-term. If it is hard to feel what is happening, take a video. See if there is a visual difference between the two variations. You may even notice that you think you’re keeping your neck long, but really your eyes are looking down and your chin progressively goes up as you squat down. This means your body was still trying to get creative.

5. Activate your feet and toes when squatting

What are your toes and feet doing?

The other cue that will often come into play in squats is to shift your weight back into the heels so much that your toes lift up. It’s true that some people will try to make all leg exercises quad exercises and lose the heaviness in their heels. This limits eccentric lengthening of the back side of their legs, contributing to knee pain. However, sometimes things get taken too far in the other direction. The problem with encouraging lifting toes is you lose the connection to your arches. This lifting up of the toes can often follow the superficial front fascial line to encourage more hip flexor activity, which pulls the pelvis into more of an anterior pelvic tilt and your spine into extension, so you tend to lose your core bracing.

Try it out

Try doing a squat slowly, and exaggerate lifting your toes up. What happens? Now compare that to going through the full movement while spreading your toes, pressing your big toe down into the ground (not scrunching), and pressing the base of your pinky toe down while making the back of your heel stay heavy. Do you feel your lower abs more? Do you feel your glutes more?

We might have exposed a weaker link by actually stabilizing with your core instead of your paraspinals (long back muscles) and using your glutes (which could be weak at eccentrically lengthening) instead of just using quads, so you might not be able to go as far. However, assess what feels different in your body and what you feel working, realizing the more you can make every part do its job, rather than just making the move happen, the less likely you’ll get overuse injuries. Remember, if you have a hard time feeling any change, record yourself on video and see what shows up there.

LOOKING BEYOND THE CORE TO PREVENT BACK PAIN:

Now that we’ve established our foundation, let’s look above and below that, assessing mobility limitations that could be contributing to your low back pain in a squat. Mobility is not just range of motion in a joint or muscle, but the ability to control that movement under load. Looking at how an area moves without a load is a good place to start, allowing you to assess whether or not you need to tackle the lower hanging fruit of improving isolated joint movement first. If you don’t move well under unloaded conditions, then that motion will come from somewhere else moving through the path of least resistance and putting increased stress elsewhere.

Next, being able to control joint mobility while under load is the strength component of mobility. What makes squats so challenging is that it requires controlling the movements in various ways through multiple joints in a coordinated manner. Without good stability, timing and sequencing in the movement, you lose the ability to maintain your stacked position of rib cage over pelvis and core engagement, contributing to low back pain as well as hip and knee pain.

With all of these, assessing for asymmetries can be important as well. If you have right and left imbalances, this can create relative rotations in your body as you load both sides at the same time. One side will move ahead of the other or shift to compensate for a limitation, creating torque through your lower back and SIJ. Continuing to work on this squat pattern without looking at the individual parts will compound those imbalances, so working on the asymmetries first is important.

Ankle mobility

What is your ankle range of motion like?

Ankle and achilles length can often be blamed for limitations in a squat because that is where stiffness might be felt. However, often it’s because pelvic stability is lost, whether through core control or ability to eccentrically load hips, and extra range or tension is put on the ankle joint. We can take the rest of the body out of the picture and just assess ankle mobility, determining if it truly needs to be worked on or if our efforts are better spent cleaning up higher up in the chain. If ankle mobility is limited, that can affect how you load through your pelvis, so addressing it can help. You can assess ankle dorsiflexion range of motion and tibial internal rotation range of motion.

Ankle dorsiflexion

For ankle dorsiflexion range of motion, get into a half kneeling position with your front foot (the foot we are assessing) 5 inches away from the wall. Next, keep the back of your heel heavy, pelvis square to the wall (no twisting), knee aiming over 2nd and 3rd toes, and slowly lunge forward to assess your ability to take your knee to the wall. If range is limited or any compensation occurs, this tells you that your ankle range is limited, affecting how you load up the chain in a squat, and needs to be worked on. You can use a slightly elevated wedge or shoe with an elevated heel to allow you to squat in the limited range, but it’s important to work toward using fewer props to have good balance in your system. If you can get your knee to the wall, this tells you that any ankle restriction you feel in a squat is coming from dysfunction higher up in the chain, and that’s where you need to focus your accessory work.

Tibial internal rotation

Another less often assessed range of motion is tibial internal rotation. The tibia has a slight range of motion and ability to pivot and twist, creating a lock and unlocking mechanism in your knee. To assess, you can sit with your feet on the floor and knees in line with your hip. Without letting your knee move and while keeping your entire foot flat on the ground, pivot your entire foot and shin as a unit inward (the movement is driven from the medial hamstring and not your arch). Full range of motion is when your pinky toe passes the midline of your knee. Often people will compensate by losing the grounding of their big toe, driving the movement from their ankle instead of the tibia, and creating a torque in their knee. Improving tibial internal rotation range of motion can often allow us to access a tripod foot more easily, setting up a good foundation from the ground to load on, as well as allowing the knee to unlock as you lower down into a squat. We can often have compensatory excessive tibial external rotation and limited tibial internal rotation due to hip and pelvis positioning, so it’s also important to make sure the hip and pelvis are setting a good foundation from above to help the tibial internal rotation range stick.

Hip and knee mobility

How do you move when not under load?

Rockbacks are a great exercise for assessing lower body mobility in an unloaded pattern and to learn how to maintain rib cage over pelvis positioning to eccentrically load glutes.Mastering the movement on the ground is a key first step to then take that movement into an upright position.

Shoulder mobility and control

Can you move your shoulder blade independently of your spine and ribs?

An often underlooked body part in a squat is the shoulder and scapula. Again, remember if you don’t have good mobility or control in one part of the body, your body will compensate elsewhere to make the movement or position happen. For a front rack position you need good scapular upward rotation, and for a back squat, good scapular retraction and depression is needed to support the weight. Both movements need to be obtained without compensation through thoracolumbar spinal extension or rib flare while still being able to keep the front chest wall open to avoid losing the rib cage over pelvis position.

Not only do we need the passive ability to get into those positions, but also strength from serratus, lower traps, and lats to be able to hold the position under increased load. The serratus connects into our external obliques and provides support to our abdominal muscles, and the lats connect our upper body to our lower body, contributing to pelvic stability. Weaknesses in either can result in overuse of the pecs or paraspinals, resulting in either too much spinal flexion and compression or spinal extension and rib flare. Improving their strength and function will help provide our lower body with a better foundation from which to eccentrically lengthen and contract.

This is just a start to look at your foundation. From here, you can go into further assessment of isolated muscle function, movement patterns, and asymmetries in our bodies that have gone too far. Hopefully this gives you some food for thought during your next workout, scanning your body for potential sneaky compensation patterns that are progressively wearing your body down and to help you to prevent back pain.

People often say going to the gym is a good break from thinking. But unfortunately, not thinking is where we can get hurt. Instead, use it as a time to not think about things outside of the current moment, and be present in the thing you are currently doing. Use it as movement meditation -- directing those thoughts toward a much-needed conversation with your body, where both sides get to talk and listen. Remember to turn inward and really assess what you’re feeling and which muscles you’re using, as well as turning outward to look in a mirror (or recording) to see if the glory you’re visualizing in your head is really what’s happening. Things don’t always have to be perfect, it’s about intention and remembering your goal for the movement to help you achieve success. Keep in mind we should leave the gym feeling better than when we came in. Happy moving!

This article was written by Anna Hammond, an amazing Physical Therapist that works at Core Exercise Solutions. You can find out more information about Anna here.

Pelvic Floor and Diastasis: What You Need to Know About Pressure Management

Join us today for this 6-part Pelvic Floor and Diastasis Video Series, absolutely free.

This course is designed for health/wellness professionals, but we encourage anyone interested in learning more about the pelvic floor and diastasis to sign up.

We don't spam or give your information to any third parties. View our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.